.

You might be wondering why I, a tech columnist, would write about tipping. The reason is that tipping is no longer just a socioeconomic and ethical issue about the livelihoods of service workers.

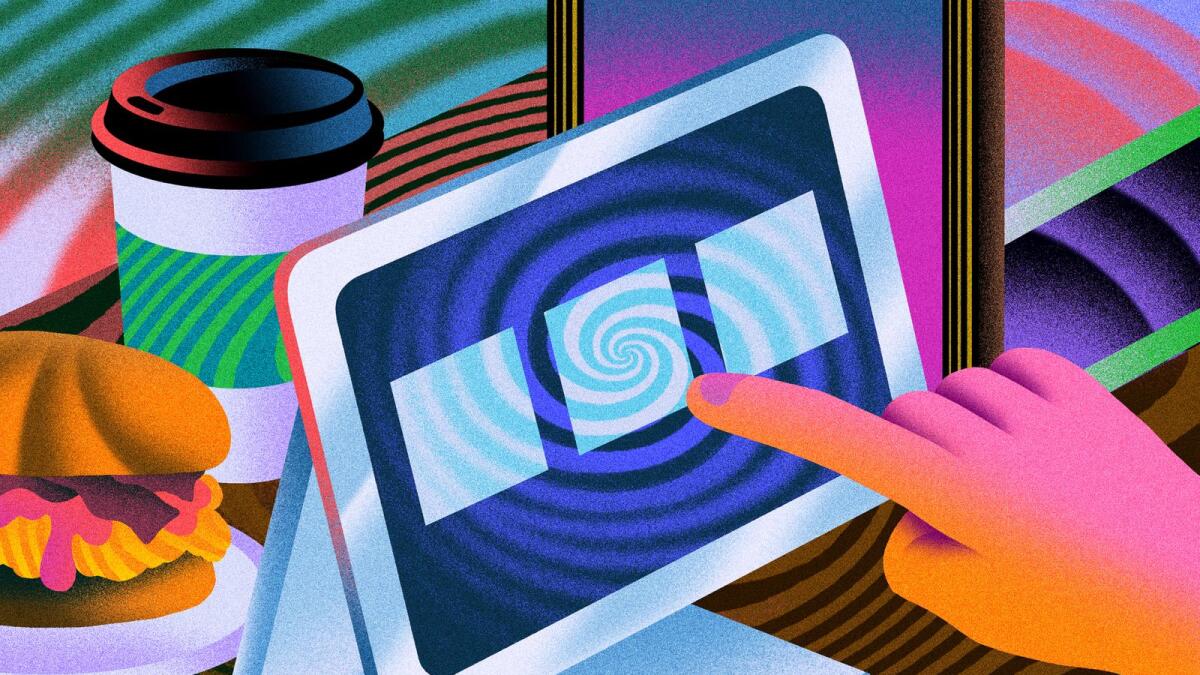

It has also become a tech problem that is rapidly spiralling out of control, thanks to the proliferation of digital payment products from companies like Square and Toast. Since payment apps and touch screens make it simple for merchants to preset gratuity amounts, many businesses that didn’t ordinarily ask for tips now do.

And many consumers feel pressured to oblige or don’t notice the charges. This phenomenon — known as “guilt tipping” — was compounded in recent years when more privileged professionals shelled out extra to help essential workers weather the pandemic. But even as businesses have somewhat returned to normal, the gratuity requests have remained steadfast.

Tipping practices may become part of a broad government crackdown on so-called junk fees, extra costs that businesses tack on to products and services while adding little to no value. The Federal Trade Commission, which announced an investigation into the practices last year, said people could experience “junk fee shock” when companies used deceptive tech designs to inflate costs at the end of a purchase.

I have felt the pain and awkwardness of seemingly arbitrary tip requests. I was recently taken aback when a grocery store’s iPad screen suggested a tip between 10 per cent and 30 per cent — a situation that was made more unpleasant when I hit the “no tip” button and the cashier shot me a glare.

When a motorcycle mechanic asked for a gratuity with his smartphone screen, I felt pressured to tip because my safety depended on his services. (It still felt wrong, because I had already paid for his labour.)

I shared these instances, along with stories I had read all over the web about consumers outraged by abnormal tipping requests, with user-interface experts who work on tech and financial products. All agreed that while it was good that payment services had increased gratuities for service workers who rely on them, the technology created a bad experience when consumers felt coerced by businesses that didn’t normally expect tips.

“If your users are not happy, it’s going to come back and bite you,” said Tony Hu, a director at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who teaches courses on product design. “Ideally, they should be tipping for an excellent experience.”

Based on my conversations with design gurus, there’s an upside to all of this. If we focus on the tech design aspects of tipping, we can overcome the pressure of tipping in the same way that we grapple with issues like digital privacy. Let me explain.

The devil is in the defaults

In 2013, Square released a point-of-sales product that replaced cash registers by letting vendors input an order into a tablet and letting customers swipe a credit card to add their signature and tip. Square has said its products have led to big increases in tips for many businesses. Its technology has since been widely copied by many brands, and traditional cash registers are a rare sighting.

A key driver of the success of digital payment systems, design experts said, is that they take advantage of a design principle that influences consumer behaviour: The default is the path of least resistance.

Payment technologies allow merchants to show a set of default tipping amounts — for example, buttons for 15 per cent, 20 per cent and 30 per cent, along with the “no tip” or “custom tip” button. That setup makes it simplest for us to choose a generous tip rather than a smaller one or no tip at all.

Plenty of studies document this type of behaviour. Ted Selker, a product design veteran who worked at IBM, Xerox PARC and elsewhere, led past research on encouraging people to register to vote. He found that they were more likely to register if that option was preselected when they filled out applications for driver’s licences and address changes. In other words, people were much more likely to not opt out than they were to opt in.

A Square spokesperson said the company’s payment technology does not allow merchants to preselect a tip amount (except when tips are automatically added for large groups in a restaurant, an industry standard). But in my experience, some of Square’s copycats allow merchants to do so.

A broader issue remains: When businesses that don’t ordinarily get tips use technology to present a tipping screen, they require the consumer to opt out.

“It’s coercion,” Selker said.

On the bright side, the gratuity screens are not considered deceptive, said Harry Brignull, a user-experience consultant in Britain, because the “custom tip” and “no tip” buttons are roughly the same size as the tipping buttons. If the opt-out buttons were extremely difficult to find, this would be an abusive practice known as “dark patterns.”

Still, if people feel unfairly pressured into tipping in situations where gratuity is unnecessary, government agencies like the Federal Trade Commission should examine that concern through a regulatory lens, Brignull said.

The FTC did not immediately return requests for comment.

Treat tipping the way you treat tech

I recommend approaching tipping the same way that you might approach technology: Be wary of the defaults, and decide when it’s right to opt out.

In a past column, I went over the default settings that I and other technology writers always change on our devices and social networking accounts to minimise the data we share with tech companies. The moral of the story was that we can exert some control over our personal information; we just have to know where to look and do extra work.

The same principle can be applied to tipping in the digital age. When a business asks for a tip, that technology is nothing but an emotionless piece of software showing numbers. You, too, can be neutral and objective when deciding whether to tip and, if so, how much.

“They’re objectifying the transaction when the whole point of tipping is to personalise it,” Selker said. “Your mindset should be, is this really what you want to do?”

The best way to avoid feeling controlled by a screen is to tip in cash whenever a gratuity feels necessary.

If you’re unhappy about how a merchant uses tech to demand tips, you can also boycott it (though this might be impractical now that so many businesses use this tech). That’s not too different from the action of people who deactivated their Facebook accounts when they felt their privacy was violated.

Even design experts are occasionally caught off guard by the defaults on tipping screens. Hu of MIT said he had recently been presented with tipping options of $1, $3 and $5 after a $10 Uber ride. He chose the middle button, $3, before realising he would normally tip the driver 20 per cent, or $2.

“It’s psychological mind games,” he said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.